In reading an anthology called THE UNDEAD AND PHILOSOPHY, edited by Richard Greene and K. Silem Mohammad, I have a bone (or maybe an entire skeleton) to pick with the first essay, “The Badness of Undeath,” by Richard Greene. Greene has a lot of penetrating speculations to offer about why we consider undeath not only worse than being alive but a fate worse than death. One of his premises, however, strikes me as wrongheaded. At the start of his argument, he excludes vampires with souls, zombies with free will, and other nontraditional undead from the category he’s discussing. He maintains they aren’t “real” vampires and zombies. In fact, he says in so many words, “In this chapter, all vampires and zombies will be considered to be unfriendly and dangerous. Moreover, all vampires will be considered to be cursed or damned and evil by nature….”

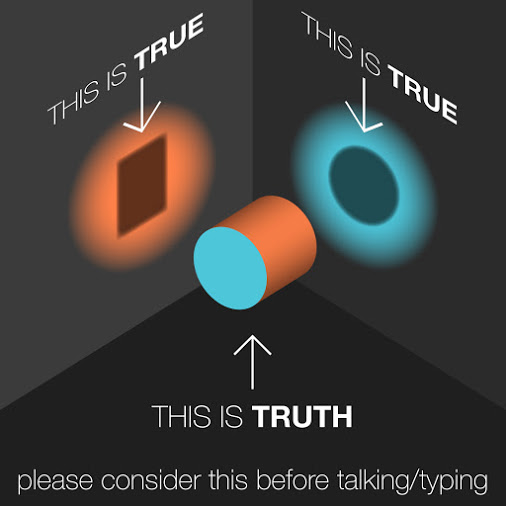

What a blatant example of “begging the question,” building the conclusion of an argument into the premise. Of course if we take as an axiom that all vampires are damned and evil by nature, regardless of its other aspects most people will see undeath as a fate worse than mere death. Greene’s approach reminds me of the “no true Scotsman” trope: A Scottish gentleman hears news of an atrocious crime committed in an English city. He says, “No Scotsman would do such a thing.” When he’s told about a similar crime in Aberdeen, he retorts, “No TRUE Scotsman would do such a thing.” It’s easy to maintain that all vampires and zombies are “unfriendly and dangerous” if we state a priori that the “good guy vampires” and kinder, gentle zombies aren’t “true vampires” or “true zombies.”

Where should the line be drawn, if anywhere, beyond which a modified monster no longer fits into its original category? Are ethically responsible vampires real vampires? Are zombies with self-consciousness and free will, as in Piers Anthony’s world of Xanth, real zombies?

As to what makes undeath, if understood in the traditional horror-fiction sense, worse than death, so far in my reading of the anthology I haven’t seen any of the authors tackle head-on the issue of the soul. They seem to equate “soul” with consciousness. Not surprising, since the book analyzes the undead in terms of philosophy, not theology. However, the question reminds me of C. S. Lewis's rationale for our fear of dead people. Why are we afraid of ghosts and revolted by corpses? Lewis suggests that because body and soul were created as a vital unity, their separation strikes us as deeply unnatural. A disembodied spirit and a de-animated body both inspire an instinctive shudder. So a soulless body that’s still moving around is even more unnatural and therefore terrifying. To me, though, this argument applies mainly to zombies. If a vampire rises from the grave with free will and the same personality he or she had in life, why shouldn’t the vampire have the capacity for ethical choices? In that case, isn’t the “soul” still present in some sense? Even the first time I read DRACULA (at age twelve), I rebelled at the notion that becoming a vampire automatically changed Lucy into a fiend.

The concept of soullessness leads to another question, discussed but not settled in one of the anthology’s later essays: If the reanimated body is no longer ourselves—if our personality has vacated it—why do we feel horror at the idea of becoming a zombie or a traditional evil vampire? We haven’t become that, really, because we’ve left the building. For instance, according to the official theory in BUFFY THE VAMPIRE SLAYER, during the creation of a vampire the human soul departs, and a demon takes possession of the body. Nevertheless, when Angel gets his soul back, he suffers profound guilt for all the evil deeds he committed while “he” was a soulless vampire. The more we consider the issue, the more tangled it gets.

Margaret L. Carter

Carter's Crypt

No comments:

Post a Comment