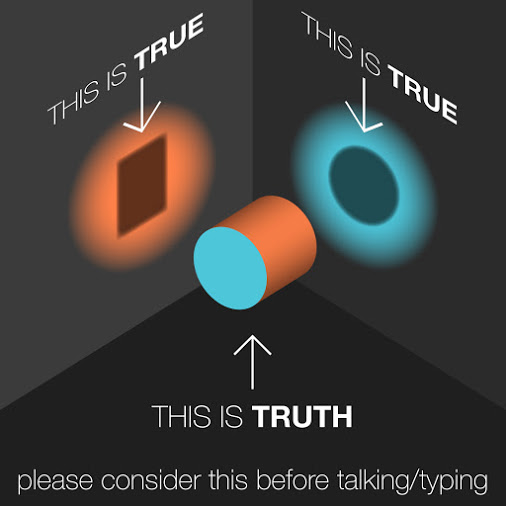

I’ve recently finished reading A QUESTION OF MAGIC, by E. D. Baker, a YA novel I highly recommend. It’s a fresh twist on the Baba Yaga legend. In this tale, Baba Yaga is a title rather than the name of a unique individual. The heroine, Serafina, gets snared into becoming the new Baba Yaga, mistress of the chicken-legged cottage, its resident talking cat, and its animated skulls. She also gets the task of answering the questions of an unending procession of visitors. The gift or curse of the Baba Yaga entails that she has to answer the first question anybody asks of her and must reply truthfully. She can answer only one query from each person, and the rules don’t allow her to ask a question of herself or prompt anyone else to ask it for her. The magic takes over her so that she speaks in a voice not her own.

Unlike the involuntary statements of the hapless lawyer in the film LIAR, LIAR, who can’t lie but speaks only truths within his own knowledge, Serafina’s answers provide information from a supernatural source beyond her. Naturally, her “gift” of the full truth sometimes pleases her questioners but often quite the opposite.

I’m reminded of a similar supernatural gift-or-curse in the book (and movie) ELLA ENCHANTED, by Gail Carson Levine. A well-meaning fairy’s spell guarantees that Ella will obey any instruction or command given to her. Like the “gift” of always speaking the truth, this spell might sound benign when applied to parent and child, but Ella reaches adulthood still having to obey anybody, no matter how careless or malicious. Unlike Serafina, who becomes a helpless mouthpiece for supernatural forces when asked a question, Ella has a bit of wiggle room to work around the conditions of her “gift.”

A different kind of obligatory truth forms the premise of an early Brian Aldiss novel, THE PRIMAL URGE. A skin patch is invented that reveals the wearer’s emotional state, mainly sexual arousal. When this device pervades society, nobody who’s attracted to another person can conceal his or her feelings. Complete “honesty” in sexual matters sounds like a good thing to many people in the 1960s world of the novel, but is it really beneficial for every fleeting impulse of that kind to be instantly apparent to all observers?

In the realm of “be careful what you wish for,” if all human beings were perfectly virtuous and kind, would universal truthfulness be desirable and unproblematic? Or would a veneer of social deceit still be justified in some circumstances?

Margaret L. Carter

Carter's Crypt

No comments:

Post a Comment